Summary

I explore in some detail, what *exactly* does “Net Zero” mean? It is glossed over by HM Gov, and nothing like as simple as National Grid presents it.

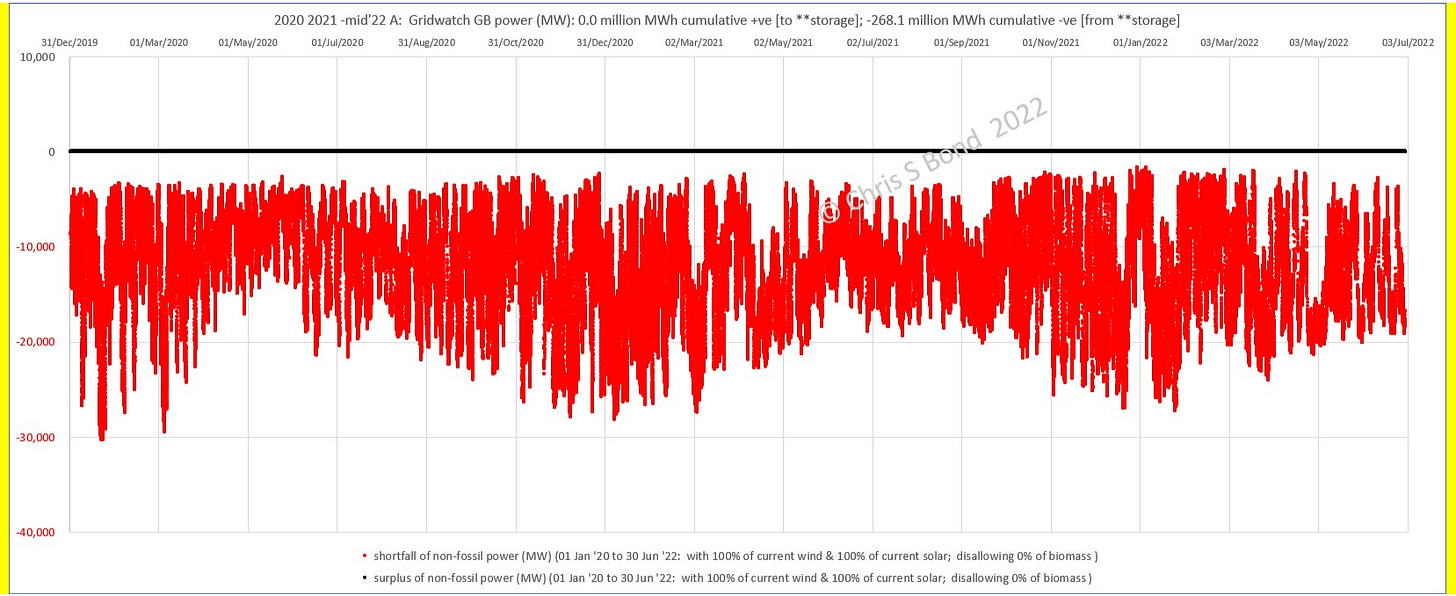

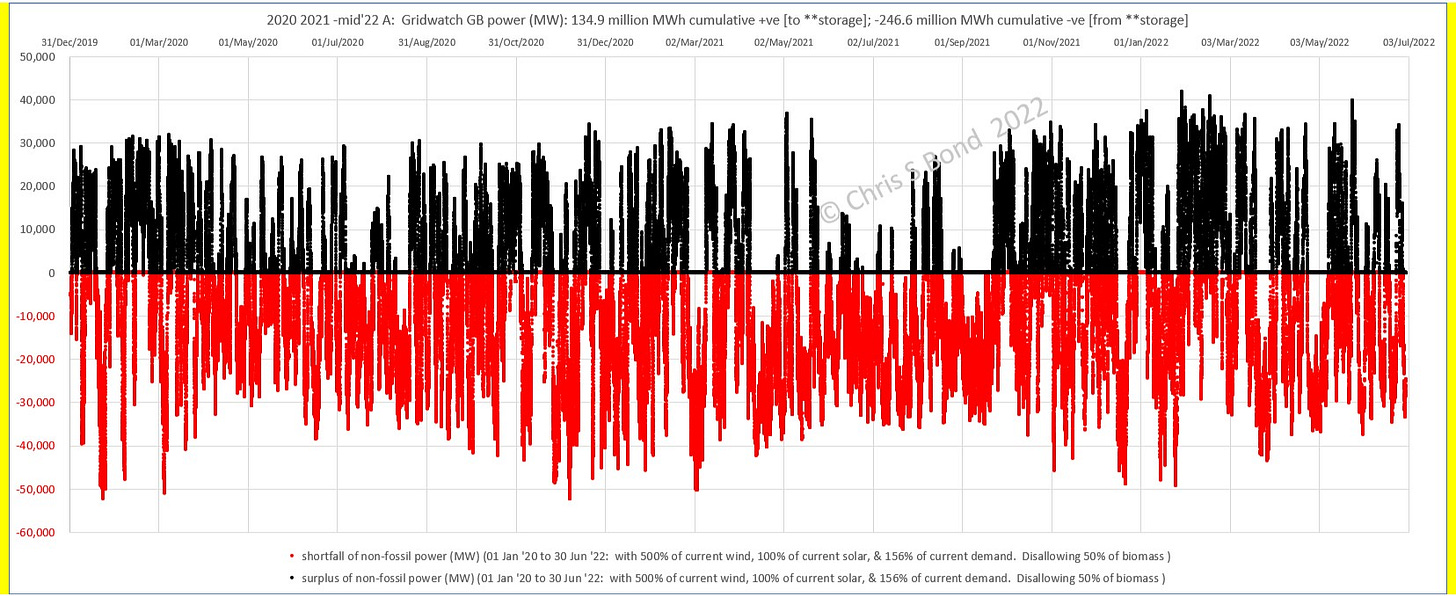

I then look at the last 2½ years’ of actual GB power data and where HM Gov’s energy ‘strategy’ might lead us. Hint: big shortfalls in renewable energy when the expected increased electrification of GB demand materialises.

I look at what might be done with surplus renewable energy - *if* we ever generate it. Hydrogen is not the easy answer some say it is.

Lastly, I look at LCOE = Levelized Cost of Energy, versus LCORE = Levelized Cost Of *Reliable* Energy, and why it matters.

Same Basis as Previously

In this post I continue to use real GB power data from Gridwatch. Later in this post I use the downloaded data for 2020 + 2021 + the first half of 2022 to show how we’re doing in the UK. To keep things human-scale I continue to use the same units: mega-watts (MW) for power flows and mega-watt hours (MWh) for amounts of energy. 1,000 MW = one giga-watt (GW) = power; 1,000 MWh = one giga-watt hour (GWh) = energy. [You will often see country-scale energy consumptions / generations cited in tera watt hours (TWh) which are millions of MWh.]

The Gridwatch power flow data is recorded every 5 minutes i.e. 5/60 of an hour. The Gridwatch power flows (MW) can thus be converted to amounts of energy (MWh) by multiplying each power by 5/60. Nearly 263,000 sets of real GB power data provide the basis of the analysis of the last 2½ years below.

What is Net Zero?

What exactly does the term “Net Zero” mean? We hear it all the time, and our commitment to achieving Net Zero by 2050 is written into our law via a barely-debated Statutory Instrument that amended the Climate Change Act 2008.

“The target will require the UK to bring all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050… Net zero means any emissions would be balanced by schemes to offset an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, such as planting trees or using technology like carbon capture and storage” [my italics]

We all probably agree that planting trees is generally a Good Thing (although planting the wrong types of trees and/or in the wrong places seems to be an Extremely Bad Thing in a myriad of complicated ways).

But what about that phrase about using technology to capture carbon? *and* storage?

We have heard of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS). It is a working technology frequently employed across the oil and gas industries, often to reduce the concentration of CO2 in produced gas to a level at which the gas can be sold as fuel. By and large the “storage” bit has comprised injecting the CO2 into an oil reservoir deep underground to raise the reservoir pressure and enhance oil recovery. Yes, the CO2 has been stored underground, but it’s been complicit in producing more fossil fuel material and so the net effect on CO2 in the atmosphere is to increase it. To avoid that, we need to store the CO2 in an ‘empty’ reservoir1.

As CCS is working technology, all we have to do is scale it all up until we are using all the oil and gas wells we won’t need any more to store all the CO2 we are capturing from our new enormous CO2 industry. Right?

Except it has not quite gone to plan in the few places it has been tried at relevant scale, for example Chevron Gorgon in Australia. Meanwhile at Shell’s tar sands facility in Canada, the 1.35 billion dollar Quest project is a qualified success: “The CCS project began operations in November 2015. It cuts down one-third of direct CO2 emissions from the Scotford Upgrader” [my italics]. Meanwhile in the coal-fired power generation world, CCS has been implemented at only two coal power plants (though one - the Petra Nova Carbon Capture Project - was moth-balled in 2020).

National Grid is our power grid operator in the UK. The power stations that feed the grid are responsible for a significant portion of our CO2 emissions and so their simple explanation of Net Zero should be illuminating. It is, however, about as misleading as it’s possible to be.

“We’ve all heard the term net zero, but what exactly does it mean? Put simply, net zero refers to the balance between the amount of greenhouse gas produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. We reach net zero when the amount we add is no more than the amount taken away. …

… What does it mean to be net zero? … Net zero means achieving a balance between the greenhouse gases put into the atmosphere and those taken out.

Think about it like a bath – turn on the taps and you add more water, pull out the plug and water flows out. The amount of water in the bath depends on both the input from the taps and the output via the plughole. To keep the amount of water in the bath at the same level, you need to make sure that the input and output are balanced.”

[My italics. Also, note to any American readers: ‘tap’ = faucet.]

Note to National Grid: CO2 is a gas, water is a liquid. That makes your tap versus plug analogy downright dishonest.

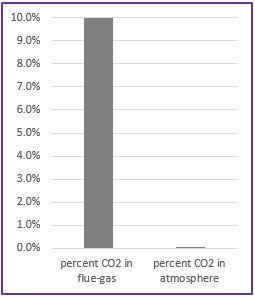

The main driver for increasing global temperatures in industrial times is generally accepted to be the increasing concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere.

However, CO2 currently comprises 419 parts per million (419 ppm) in air. That is just 0.0419%. Compare this with the percentage of water vapor in air: 4.24% when the dew point is 30 °C (86 °F). In other words, the concentration of water vapor in the air just above a bath at 30 °C is about 100 times that of CO2 in the atmosphere. If National Grid said that Net Zero could be achieved by balancing the inlet water via the taps with the vapor (steam) lost through evaporation, it would be more analogous to the task of balancing CO2 in the atmosphere.

Do try this at home.

With the bath plug in, turn the hot tap on and stop the water level rising by blowing on the surface of the water to force evaporation.

*So* much harder than just pulling out the plug.

For the CO2 ‘bath level’ i.e. the level of CO2 in the atmosphere, many of the largest ‘tap’ streams are flue gases from power stations and industries. They have high concentrations (typically 10-15%) of CO2 depending on the fuel being burnt and application. Once dispersed into the atmosphere the average concentration is 0.00419%, or around 240 times less.

We’ve already seen how difficult it is in grid-scale facilities to remove even 90% of CO2 from concentrated flue gas.

Of course, carbon capture from flue gas and its permanent sequestration - *if* CCS can be made to work - reduces the flow of CO2 *into* the atmosphere. It does nothing to remove the CO2 already there.

The extreme dilution of CO2 in the air is why Direct Air Capture (DAC) of CO2 is thermodynamically a non-starter. Unless, that is, you have lots and lots and lots of solar-powered things with huge areas of thin surfaces specially adapted over millions of years to perform this magic.

And even then they may each only absorb an average of 10-20 kilograms per year. After which you have to find a way to stop them re-releasing all their collected CO2 when they die. Biochar, anyone?

This is a bit of a dilemma for HM Gov. However, The Institute for Government offers a possible get-out from this bind:

“Net zero refers to achieving a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. There are two different routes to achieving net zero, which work in tandem: reducing existing emissions and actively removing greenhouse gases.

A gross-zero target would mean reducing all emissions to zero. This is not realistic, so instead the net-zero target recognises that there will be some emissions but that these need to be fully offset, predominantly through natural carbon sinks such as oceans and forests” [my italics]

All that HM Gov needs to do, then, is to engage lots of foreign entities to solve our CO2 problems for us **. There will be offset schemes in far-away places, certified CO2-eating oceans, lots of certified forestation. The propriety of which we will trust implicitly because there is absolutely no money involved in any of this to incentivise dishonesty. And no competition from all the other countries trying to achieve their versions of Net Zero.

[Sarc font]

** much as they have done with recycling

[Sarc font again]

Alternatively, absent miraculous CO2-sucking technology yet to be developed, the legal target is actually for GROSS ZERO. HM Gov just haven’t admitted it to us / even realised it themselves yet.

GB 2½ Years 2020 - 1H 2022

With the actual wind and solar generation patterns from the last 2½ years we can model HM Gov’s ‘plan’ [stop laughing at the back] by increasing wind capacity to 500% of its current level. I keep solar capacity the same, while I disallow 50% of biomass (because I am unconvinced it is truly ‘green’ or carbon-neutral).

Of course, over the next several years we are all meant to be electrifying home heating and cars, so demand for power will rise. According to McKinsey in their February 10, 2022 Article, the electricity sector demand will increase by 56% by 2035. (By then perhaps we’ll have two or three Hinkley Point C’s-worth of new nuclear power, but that will mainly offset the existing nuclear power due to be shut down at end-of-life.) So let’s see what we get when we increase in power demand by 56% while adding all that extra wind generation *capacity*.

In this chart red = failure to keep the lights on. HM Gov’s ‘plan’ would leave us in the dark for far too much of the time for my liking.

Hydrogen to the Rescue?

There is a *very* active hydrogen lobby across many parts of the world. They appear to have the ears of many governments and are receiving large quantities of tax-payers’ largesse courtesy of far too many innumerate / scientifically-illiterate politicians.

I mostly agree with the conclusions of the Hydrogen Science Coalition on this. If we can make ‘green’ hydrogen using renewable power to electrolyse water, that ‘green’ hydrogen should be used, for example, to make ammonia and thence urea for essential fertiliser to keep feeding the world’s population. Use ‘green’ hydrogen preferentially for that and other hard-to-decarbonise processes and you would displace ‘grey’ hydrogen and truly reduce CO2 emissions. The lobbyists want us to instead use hydrogen mixed into methane for fuel: this is as stupid as burning £20 notes to keep warm for all the reasons given by any engineer who has crunched the numbers.

We can only make ‘green’ hydrogen when we have surplus renewable power. That presents a dilemma. The investment in the kit (electrolysers, hydrogen clean-up and compression, etc.) would be immense, but it would be stop-starting randomly. That could be smoothed out (a bit) using electrical storage, but as I’ve said in my previous posts the scale of that would also be immense.

Other shades / colours of hydrogen produced from fossil materials? Hugely inefficient wastes of energy and almost certain to continue to contribute to emissions of gases that will continue to increase warming. Burning £50 notes to keep warm.

Ah, but couldn’t we use surplus nuclear power in the electrolysers to keep them running continuously? Oh the stupid, it burns! So much energy is lost when splitting water into H2 plus O2, the absolute last thing you want to do in an energy-constrained world is waste good reliable carbon-free nuclear power.

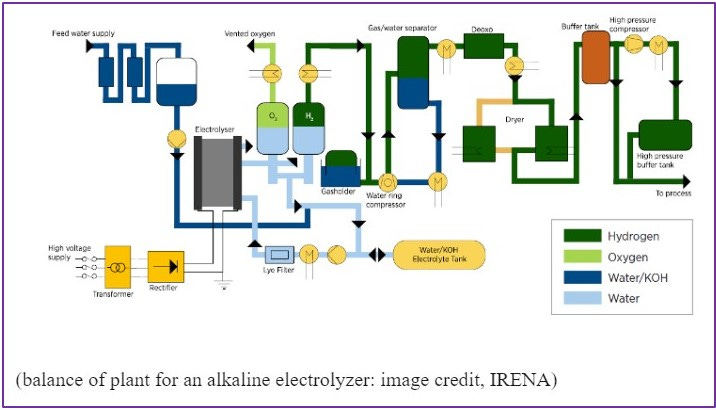

So, potentially we are back to intermittently running electrolyser systems. These are more complex than multitudes of electrolyser stacks. See, for example, Paul Martin’s excellent write-up here. I have borrowed Paul’s simplified flow diagram below. This only shows the main component types (the various pots, pans and other equipment). It does not show all the instruments, controls, safety systems, etc., etc. for what would be an inherently high-hazard facility.

There is also general agreement that leakage of H2 into the air can itself contribute to warming, and most people know that transporting or storing hydrogen is difficult. So it would make sense to site these facilities close to the hydrogen consumers. But most large-scale industrial consumers (ammonia plants, steel works, etc.) would not be able to operate on intermittent hydrogen flows, so substantial volumes of buffer storage would be necessary: yet more complication and enormous expense.

No, hydrogen is not the easy answer the lobbyists would have you believe.

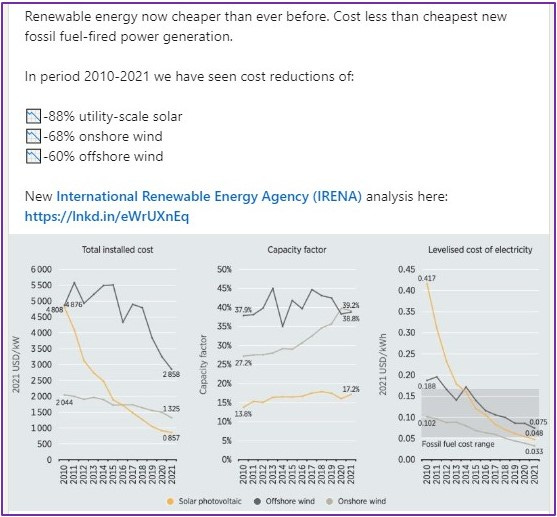

LCOE versus LCORE, and Why it Matters

Some of you may have seen my comments on LinkedIn responding to boosterish posts e.g. below saying “renewable energy is getting cheaper and cheaper, look at the LCOEs since [insert long-ago year here].” (LCOE is Levelized Cost Of Energy.)

Various comments have been made to me to the effect that I should just stop quibbling, we need to get on with it, it has to be done *right now*.

The thing that troubles me is that we are at risk of being swept along on a tide of Groupthink with few of the negatives being interrogated. (When I say we I mean our governing classes and their politics grad advisors.) We already have indications from around the world - Texas, Australia, the UK - that reduced resilience in our power systems can lead to power failures / brownouts / blackouts. For many people that may only be an inconvenience: they may have to delay charging their EVs or their iPhones for a few hours. But for everyone who is dependent on continuous power it can pose a serious threat to their health.

As renewable energy sources displace dispatchable fossil and even nuclear generation, the system costs (if loaded solely onto the legacy generators) makes them less economic. For example this 2012 study issued by the OECD / NEA gave this warning:

“This report addresses the increasingly important interactions of variable renewables and dispatchable energy technologies, such as nuclear power, in terms of their effects on electricity systems. These effects add costs to the production of electricity, which are not usually transparent. The report recommends that decision-makers should take into account such system costs and internalise them according to a “generator pays” principle, which is currently not the case. Analysing data from six OECD/NEA countries, the study finds that including the system costs of variable renewables at the level of the electricity grid increases the total costs of electricity supply by up to one-third, depending on technology, country and penetration levels. In addition, it concludes that, unless the current market subsidies for renewables are altered, dispatchable technologies will increasingly not be replaced as they reach their end of life and consequently security of supply will suffer. This implies that significant changes in management and cost allocation will be needed to generate the flexibility required for an economically viable coexistence of nuclear energy and renewables in increasingly decarbonised electricity systems.”

Also: “… some general trends can be clearly identified and a number of important conclusions can be drawn. First and most importantly, the system costs for integrating variable technologies into the electricity system are large: total grid-level costs lie in the range of USD 15-80/MWh [as of the 2012 study], depending on the country and on the variable technology considered. Among renewable technologies, wind onshore has the lowest integration costs, while those of solar are generally the highest. Results also confirm that grid-level system cost may increase significantly with the penetration level of renewables.” [My italics]

This is exactly why I think we should be referring to LCORE = Levelized Cost Of *Reliable* Energy.

But, say objectors, then you have to load all the carbon removal costs onto the fossil generators so you’re back where you started, hah! My issue with that view is that, with or without carbon removal equipment, a fossil generation plant will continue to produce power to keep the lights on 60/24/365. (Actually, carbon capture and sequestration is energy intensive so it would consume 25-30% of the power output.)

It would all be slightly less bad if our current direction of travel looked like it was going to succeed, but it doesn’t. It would also be less bad if we weren’t all soon going to disappear under mountainous energy bills and higher costs of living, but we are.

Rather than an energy transition I think we are heading for an energy cliff.

I think we should slow or even pause our attempts to reach “Net Zero” until we have proven technology at scale that will achieve the aims without bankrupting us.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed are solely my own.

This material is not peer-reviewed: my readers are my reviewers.

I welcome your feedback - polite factual comments and reasoned arguments please.

When oil and gas people refer to a ‘reservoir’ they mean porous rock capped by impervious rock layer(s). Volumes underground are immense, and so oil or gas volumes trapped in the pores and fissures can be substantial. Eventually production from a reservoir ends (just when, is highly-dependent on the value of the hydrocarbons as well, sometimes, as the political pressures applied to a national energy company). Then that reservoir is considered ‘empty’ - although it might actually be full of water pumped down to enhance oil recovery in later stages of production - it *may* be suitable for injection and sequestration of CO2.

To quote my dictionary: "The concept of net zero was originally closely related to the older one of ‘carbon neutrality’, a general idea that the carbon dioxide releases associated with an activity could be offset or undone by undertaking (or paying others to undertake on your behalf) carbon-absorbing activities. Some still use this definition, but other seek to take net zero further, taking non-carbon greenhouse gases into consideration. Some go further still, rejecting science-based approaches entirely.

On the other hand, one of my panel of reviewers suggested net zero was no more than ‘a

marketing-related calculation arrived at by performing a very naive mass balance over a small,

arbitrarily defined part of a much larger system’, or to put it another way, greenwash.

However far people go, net zero remains controversial amongst some environmentalists as it is

perceived as not going far enough, whilst some trade unions have sought to harness the idea to

their own political agendas by including for example a requirement for a ‘just transition’, favoring

their members in the interim.

Perhaps a more reasonable and less self-interested criticism of net zero is it can be rather like net

present value, kicking the can of reining in carbon emissions into the future, whilst we continue

business as usual in the present.

Whatever your view of these issues, it is clear that net zero can mean a range of things, most

notably in respect of what should add up to zero, the period over which the calculation is done,

and whether or not to include the various unrelated issues which stakeholders may seek to

smuggle in alongside the actual reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. In this way it is rather

like sustainability."

Hi, I started to reply in LinkedIn but I think it is probably better to continue here.

Thanks for the link. I've read the article and it raises a lot of questions but the most important one is what is the "plan' you referred to in your reply on LinkedIn?

Is it the Sixth Carbon Budget from the CCC referred to in the McKinsey report?

I looked at the CCC site and there were three or possibly four multi-megabyte documents to download. I can almost guess from the cover graphics and the titles that they will be a hard and possibly unsatisfactory read. Maybe you can point me to a summary suitable for engineers. Maybe you have done one yourself.