For all the chatter about ‘green’ hydrogen across social media, it may come as a bit of a surprise to readers that the first plants producing this panacea [joke] have only recently begun to operate.

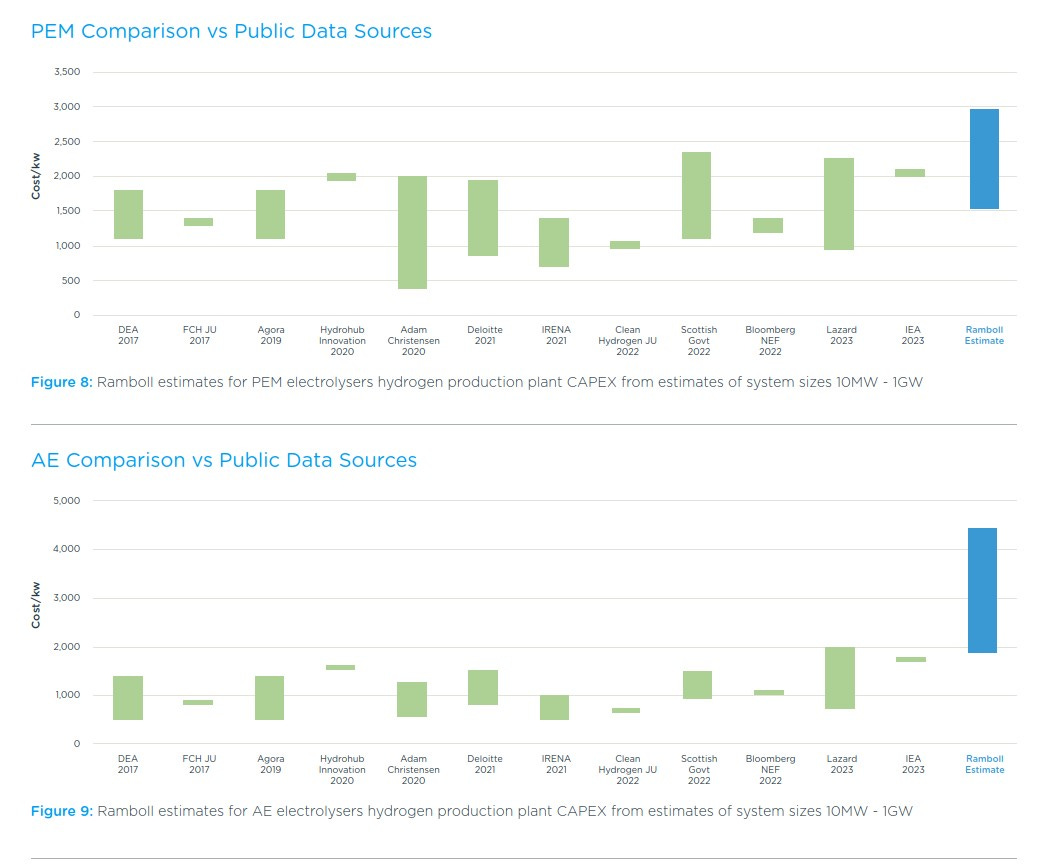

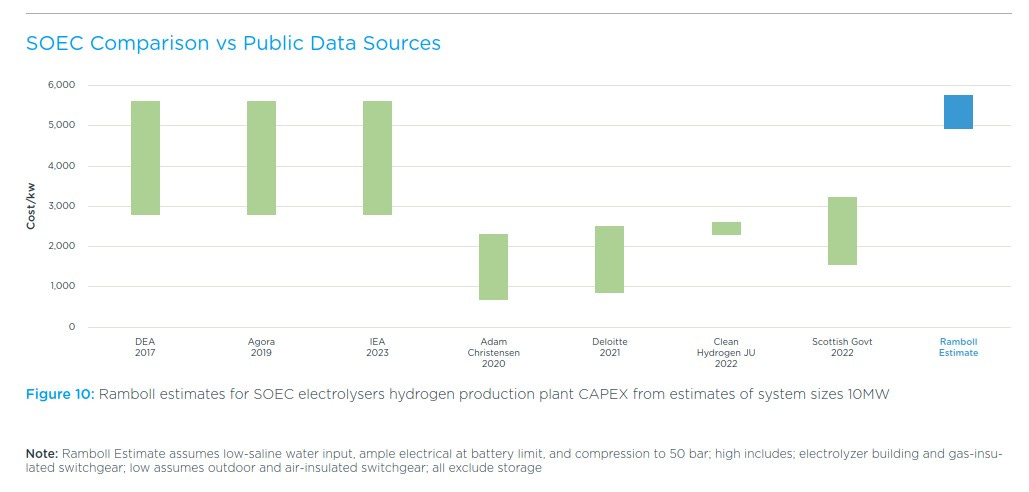

It’s a given that the first of a kind (FOAK) of anything is likely to be expensive. And it’s also a given that, as development and commercialisation continue, technology lessons will be learned and costs will fall. Quite how far costs might fall, and the reasons they may not fall as far as some hope, are covered in e.g. the "Achieving affordable green hydrogen production plants", November 2023 study by Ramboll.

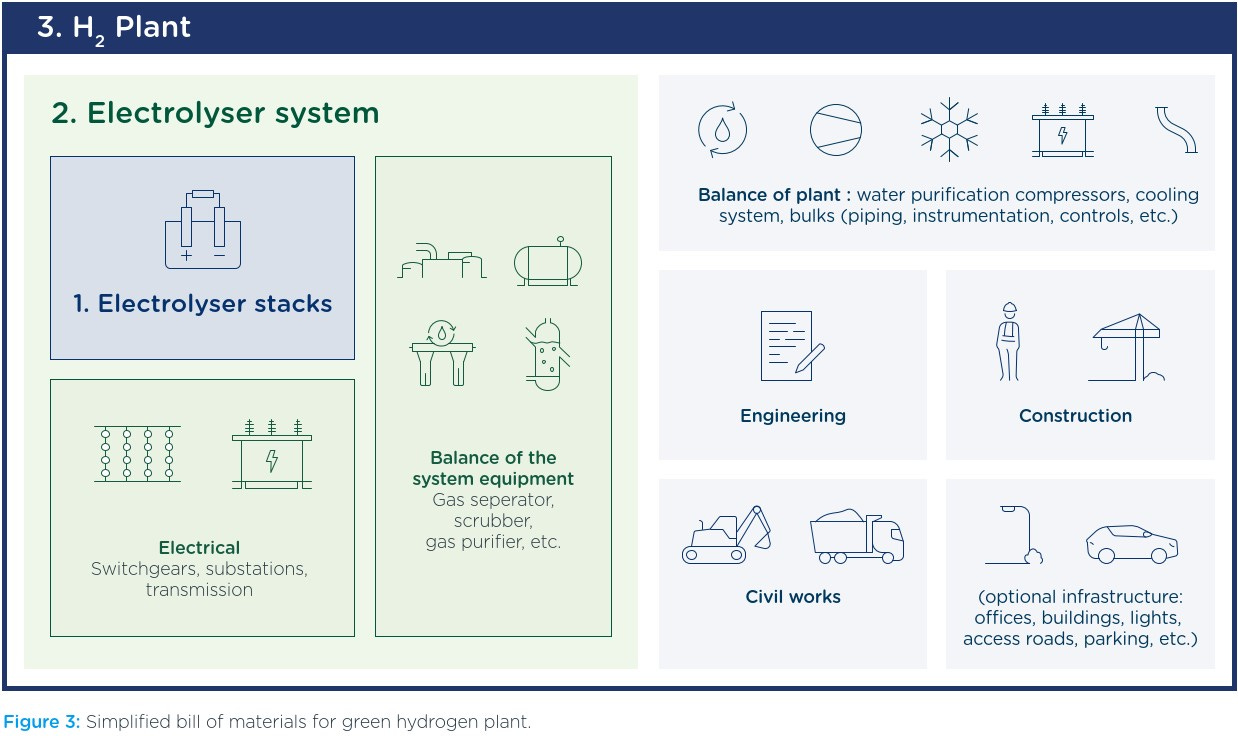

First, a reminder (Figure 1) that a plant to produce ‘green’ hydrogen comprises a lot more than the electrolyser stacks themselves. The mixture of three different types of technology is key to Ramboll’s findings: the costs of the novel electrolyser stacks may decline rapidly, but the costs of all the common electrical equipment and the process plant ‘pots and pans’ are unlikely to decline as fast or as far merely because they are being used to produce hydrogen. (In fact, competition for increasing amounts of even common materials and types of equipment would likely drive their prices higher.)

Figure 1: The Ramboll Hydrogen Plant Model

Three charts from the Ramboll study (Figures 2 A, B & C) summarise their results.

Figures 2 A & B: Ramboll Costs - PEM- and AE-Based Electrolyser Plants

Figure 2 C: Ramboll Costs - SOEC-Based Electrolyser Plants

Time will tell which among the entities listed on Figures 2 is more correct as regards the costs of producing ‘green’ hydrogen per kW. I’m more interested in some early signals from two actual plants regarding operation/operability.

Sinopec’s 260MW Kuqa Facility, China

The ‘green’ hydrogen production facility at Kuqa in Xinjiang was originally intended by Sinopec to be powered completely by Solar PV. Then in June 2022, Recharge News © revealed that the solar farm had been scaled back from the ~1,000 MWp *capacity* originally planned, to the 361 MWp *capacity* that was actually built. This, according to Recharge News, could provide “58% of the electrolyser’s 1,060 GWh annual power requirements” (I would emphasise this is only true “on average”). The remaining approximately 42% of power required? It may be from wind, it may be from coal, it may be from some other mysterious ‘green’ source, we just don’t know, says Sinopec as cited by BloombergNEF in the article.

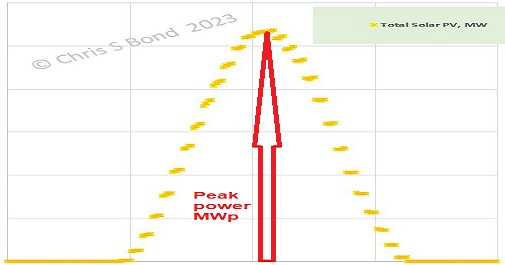

I include Figure 3 to remind readers that a Solar PV array can only deliver its design peak power (designated “MWp”) sometime in the middle of the sunniest of sunny days, and it diminishes to near-as-dammit zero every night. I use *capacity* for ‘renewables’ for similar reasons: they have a maximum design power output, but what they might deliver at any given moment is in the lap of the gods.

Figure 3: Generic Solar PV Power Generation Across 24 Hours

So, the Kuqa plant was designed for intermittent power availability, with product hydrogen buffer storage (the photos show ten pressure spheres).

Then the © story broken 11 December 2023 by Hydrogen Insight indicates that the three different vendors of alkaline electrolysers at this plant have produced electrolyser stacks that are incapable of safe operation across the full turndown range of input power specified in the design. We’ll come back to what is meant by “safe operation” shortly.

Another snippet from the Recharge News article is that Sinopec saved some upfront cost at Kuqa by constructing the plant in 40MW modules each comprising eight 5MW electrolyser stacks. Each module then shares common gas and liquid separation units and purification unit, which may further contribute to reduced plant turndown capability.

The Sinopec Kuqa hydrogen plant was designed to supply hydrogen to the nearby Sinopec oil refinery (at grid coordinates 41.709, 83.045) to displace the ‘grey’ hydrogen from its steam methane reformer (SMR).

For me the truly boggling aspect to the story is that the SMR was shut down by the refinery before the novel technology of the upstream hydrogen plant was fully demonstrated. Whoever signed off on that decision will be unpopular - not a good thing to be in the CCP’s China.

This leaves the downstream refinery short of hydrogen to desulphurise its products, heaping pressure on the hydrogen plant to quickly sort out its issues (which potentially include a shortage of sufficient ‘clean’ power)….

Oh look, there’s a connection to the local power grid… that’s got lots of spare power flowing through it 24/7, let’s just use some of that.

Which is why, unless this is not a possibility, I think the question of the new era will be “How Green is my Hydrogen?”

By contrast, there is this.

Iberdrola’s 20 MW Plant, Puertollano (Spain)

Ok, it’s a tiddler by comparison with the Kuqa facility. But it still provides some useful information.

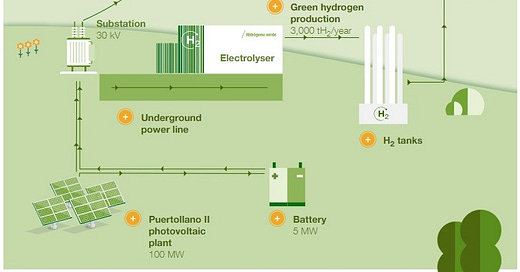

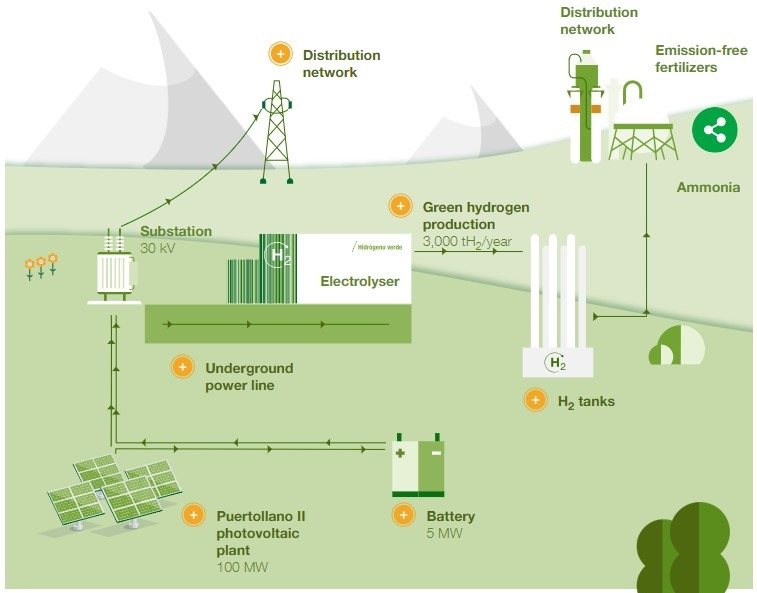

“Iberdrola has commissioned the largest plant producing green hydrogen for industrial use in Europe. The Puertollano (Spain) plant consists of a 100 MWp photovoltaic solar plant, a lithium-ion battery system with a storage capacity of 20 MWh and one of the largest electrolytic hydrogen production systems in the world (20 MW). All from 100% renewable sources.”

“With an investment of 150 million euros, the initiative will create up to 1,000 jobs (700?) and prevent emissions of 48,000 tCO2/year (39,000?). The green hydrogen produced there will be used [in] Fertiberia's local ammonia plant.” “Thanks to this technology, it will be able to reduce natural gas requirements at the plant by over 10%”

As is often the case, the number of jobs (which varies depending on which Iberdrola source you look at) seems to have been inflated by including the personnel required during the construction phase. (Either that, or that’s one heck of a make-work scheme for the locals.) And I’m glad I’m not a shareholder in Iberdrola if that’s how they splash their cash.

The simplified flow-scheme is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: The Iberdrola Hydrogen Plant, Puertollano

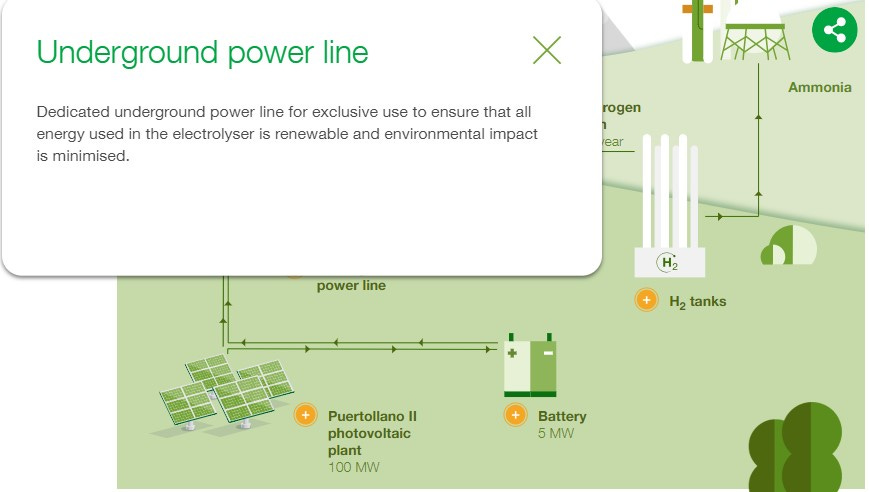

Interestingly, the underground power line is to “ensure that all energy used in the elecrolyser is renewable”, per Figure 4 A.

Figure 4 A: Dedicated Power Line

This gets around the conundrum illustrated by the Kuqa facility. Iberdrola’s hydrogen will be able to demonstrate its ‘greenness’.

Whether this constraint will render the Iberdrola hydrogen plant uneconomic? Again, time will tell.

“Safe Operation”?

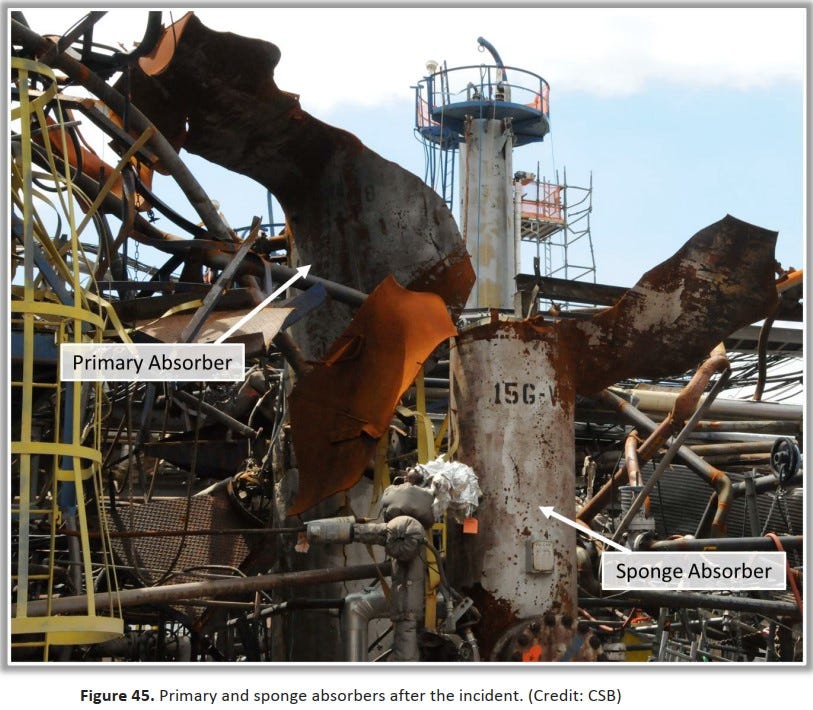

At low power flows the electrolyser stacks in the Kuqa plant are stated to produce higher concentrations of oxygen in the product hydrogen than is ‘safe’. Of course the design limits are set to provide significant safety margins for alarms and automatic trips, etc. But if all safety measures fail the ultimate worst-case result when process equipment is filled with a mixture of flammable gases was illustrated in the Husky Superior Refinery explosion of April 26 2018, as reported by the US Chemical Safety Board (CSB).

"… the incident occurred while the refinery was shutting down its fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) unit to perform planned maintenance (called a “turnaround”), a common refining process. Two vessels in the FCC unit exploded, propelling metal fragments up to 1,200 feet away..." [~400m]

"The sponge absorber pressure continued to decrease during the hour leading up to the explosion and had reached 166 psig. [~11½ atmospheres.] Then, just before 10:00 a.m., the primary and sponge absorber vessels exploded."

"The two vessels that exploded both had a design pressure of 250 psig." [~17 atmospheres.]

I suggest this is all sufficiently close to hydrogen plant parameters for some of the lessons learned to be applicable.

CSB Figure 45: Not “Safe Operation”

And on that sobering thought, I’ll wish you all a very Merry Christmas and I’ll be back in the Happy New Year!

Always worth remembering Shell's REFHYNE project at Wesseling refinery.

https://www.refhyne.eu/publications/

The Lessons Learned and the Policy Report repay download and reading. It's not a pretty picture, and expensive natural gas seemed only to make the electrolysis less economic.

Also worth watching is PosHYdon - which has now had to be bailed out by the Dutch government, although they are putting plenty of spin on that. It is supposed to run only when a particular wind farm is operating. But they are a long way behind, and now want to test the systems onshore first!

https://poshydon.com/en/dutch-state-joins-offshore-green-hydrogen-pilot-poshydon-via-ebn/

What do you think of using wet cycle combustion of metal powder to produce hydrogen instead? I make super cheap aluminium powder in Australia, send it to Japan to be used for hydrogen production in ammonia plants. The aluminium oxide produced can be recycled again. That's surely more sensible than transporting hydrogen from Australia to Japan.